Technology

What to know about UVC light sanitation in face masks

The harmful radiation we ordinarily avoid could help protect us from Covid.

Experts say the spread of coronavirus variants means people need to . While doubling up is an option, as is upgrading from a cloth mask to an N95, some are emerging to take masking even further by incorporating ultraviolet-C light sanitation.

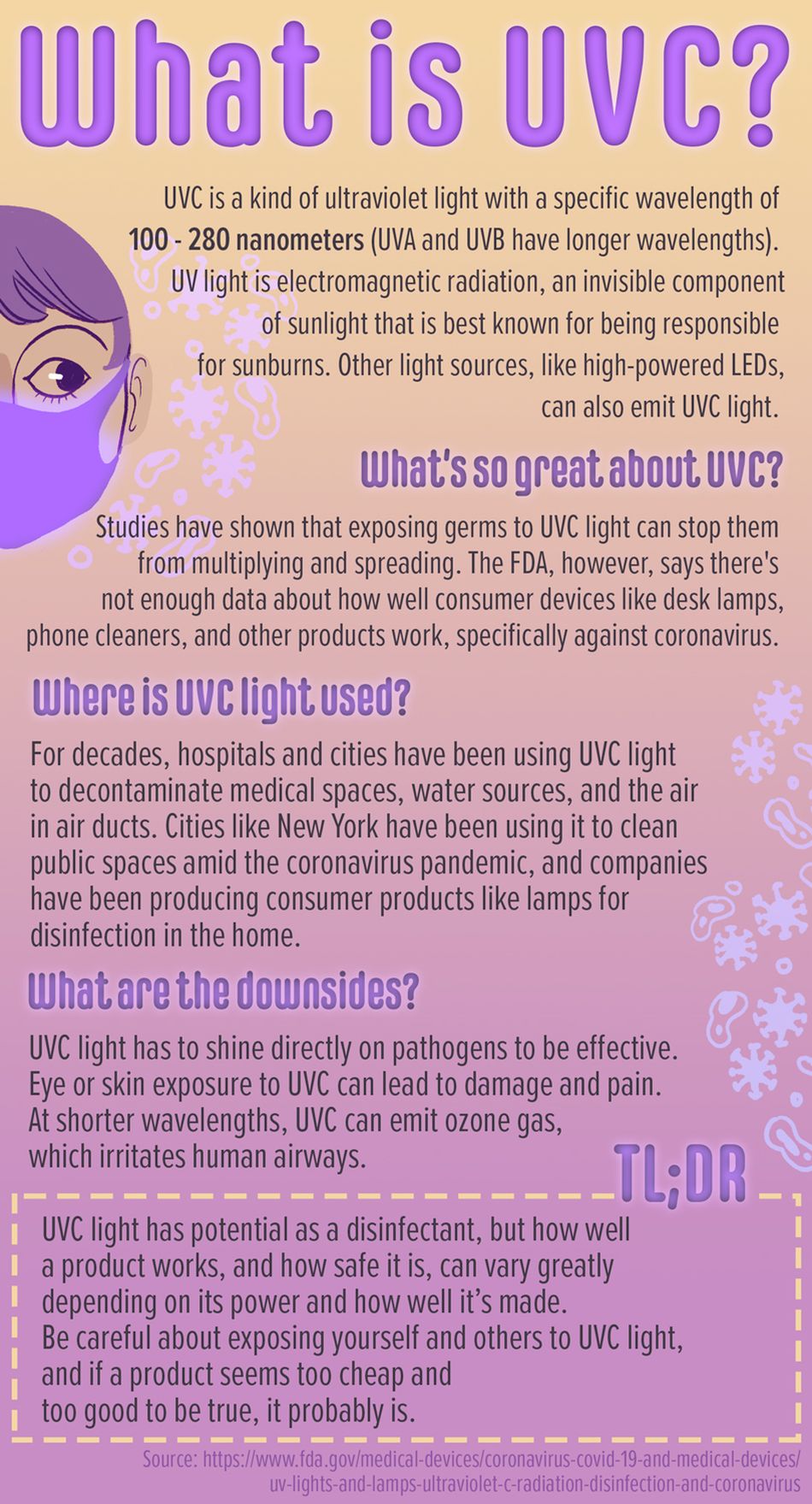

UVC light is a class of radiation with short wavelengths. It’s naturally emitted by the sun, but man-made light sources like LEDs can also be made to generate it.

While it’s harmful to humans if it reaches our skin and eyes, UVC also has the ability to disrupt the DNA of pathogens and prevent viruses from spreading. That makes it a sanitation tool that cities and organizations like hospitals have been using for years to keep public spaces and even water water supplies healthy. It’s become even more prominent recently amid the coronavirus pandemic, as cities like New York have turned to UVC to sanitize subway cars.

There’s also been a boom in consumer products using UVC. Desk lamps, cellphones, wands, and earbuds — all with the promise of protecting the user from coronavirus — have proliferated in the last year. While recent studies show that UVC light can render the coronavirus inert, the FDA warns that the quality can vary widely, and that there’s still not enough information known about how much UVC light needs to be shone and for how long in order to be effective against the virus.

That’s not to say UVC doesn’t have promise as a protective measure — it does. And some companies are hoping that potential manifests in masks.

Shining a light on masking

There are two ways companies are applying this technology to masking. The first is by blasting filters inside masks with UVC rays, which these companies say cleans the filters and keeps them effective longer (however, some studies show that UVC light actually degrades N95s). LG and other companies are making masks and UVC mask inserts that go this route, like Oracle Lighting’s A.I.R. device.

The other method is actually subjecting the air you’re about to inhale to UVC light, which ostensibly provides an extra layer of protection beyond an air filter.

One such mask is the UVMask, made by a Canadian company called UM Systems, which develops light and laser products for healthcare. The UVMask is an all-in-one mask that contains an external shell, an N95-grade air filter, and then a third layer it calls the “sterile vortex.” This is a spiral-shaped air pathway embedded with LEDs that shoot UVC light at the air as it makes its way through before you breathe it in. It’s battery-powered, with eight hours of battery life per charge, contains a fan system to keep the LEDs cool, a silicone face covering for comfort, and straps to keep nearly 4 ounces of face hardware comfortable (or so the company says).

People apparently like the idea. UM Systems launched a successful $3 million Kickstarter campaign for the UV Mask over the summer, and is currently running an IndieGoGo campaign that has raised nearly $1.2 million. Backers can pre-order the mask for $119 for estimated shipping in February.

The company claims it is the first mask of its kind, since competitors usually go the former route of sanitizing the mask filter, not the actual air. Dr. James Malley, a University of New Hampshire professor who studies UV sanitation and assesses products as part of the International Ultraviolet Association, said he has come across a handful of others that are still in the R&D phase.

“There are, in my knowledge base, six or seven of these masks at different stages of research and development,” Malley said. “Some are being done extremely well in terms of technology and understanding and R&D, and others are kind of being rushed out there. And are rubbish.”

Despite the shortcomings of some prototypes, Malley said these products have potential, and the science that undergirds them is theoretically possible, especially since advances in LED technology have allowed for large amounts of power in tiny spaces. Getting the science right, however, might be trickier than it appears; Malley said most of the products he assesses (which are not limited to masks) work about half as well as they claim to. Malley is also skeptical that adequate development and testing could have been done in time to make a product in response to the pandemic.

All you need to know about UVC

Image: vicky leta / mashable

“Consumers are inherently impatient, and good science, as we know, takes months to years to get it right,” Malley said.

UM Systems has actually been working on its UV Mask since 2018. CEO Boz Zou said the company was inspired by the SARS pandemic and the proliferation of MERS. But when coronavirus came along, UM sped up the development process and decided to take it directly to consumers with crowdfunding campaigns.

“We didn’t anticipate this,” Zou said. “But it was quite timely.”

It’s important that a UV mask also contains an air filter, since particles like dust can shield tiny virus particles from germ-killing light rays. But even if you have an initial air filter that’s able to expose pathogens, the invisible nature of UV light and air, combined with the size limitations of a mask, make in-mask air purification a hard scientific nut to crack. Malley explained that there are several challenges.

To work as a sanitizer, UV light has to be shot directly at the particles. It can’t just diffusely emit light. This means the light has to be directed in the right place, and that the air has to be trapped and follow a precise path.

“If we’re going to use UVC in a mask, we need a lot of power in a small space. That’s where a lot of these devices on the market have missed the boat. They’re selling speed to the consumer.”

The light also has to be strong and sustained. The shorter amount of time a particle is exposed to light, the stronger the light has to be. Since breathing happens almost instantaneously, in-mask UV lights have to be extremely powerful. LEDs also lose power if they overheat, so these potent lights have to be kept at a consistently cool temperature to make sure they don’t degrade. Then again, they also need enough battery to retain their strength, which, according to Malley, makes for a hard line for companies to walk.

“If we’re going to use UVC in a mask, we need a lot of power in a small space, which is called power density,” Malley said. “That’s where a lot of these devices on the market — whether they be masks, or cell phone disinfectors, or others — have missed the boat. They’re selling speed to the consumer. But we look at the power they’ve actually designed in, and it’s grossly underpowered.”

Malley also said that just assembling all of those power and cooling needs into a small space is a “big obstacle.” Not to mention it’s quite a lot of hardware to walk around wearing on your face.

The UVMask is like an onion. It’s got layers!

Efficacy is not the only challenge. UV light can also be harmful to human skin and eyes. It has to be contained securely, and not generate radiation at the lower wavelengths that can emit harmful ozone gases.

“A well-devised, well-designed, well-tested UVC mask will be fine,” Malley said. “Others that maybe aren’t could be a risk.”

That issue of testing is the final hurdle for these products. Because this product category is so new and falls somewhere between a health device (which would be under the purview of the FDA), and an environmental device (which would land at the EPA), there isn’t currently a central regulatory body that has established standards or does testing and assessment.

Zou said that proactively testing the UVMask was crucially important to his company. UM Systems addresses how it faces all of the development challenges — from ozone gas emission to power cooling — in its FAQ. Its novel “sterile vortex” design appears to meet the challenge of making sure the air goes exactly where you want it to, through a pathway totally encircled by LEDs that can blast it with UVC light.

It also hired a prominent third-party testing company called SGS to conduct efficacy and safety tests, and it has published those validations on its IndieGoGo page.

“Skepticism is healthy, or ethical, with any new technology,” Zou said. “I would advise people to really read our white paper and go through our test testing report.”

Another company, called Oracle Lighting, makes a UV mask called the A.I.R., which stands for . Justin Hartenstein, its director of product development, agreed that there are “many variables and conditions that need to be considered when it comes to the science of ultraviolet germicidal light.” Like UM Systems, Hartenstein’s company also went through SGS to validate its claims.

For people considering whether to upgrade their masks with UV light, the question is whether third-party testing — paid for by the maker of the product that’s being tested — is enough. Malley said companies that go through proper development and testing of UV products can and are coming out with devices that put the advances in LED technology to great use. But there’s also a “regulatory abyss,” as he put it, that makes for a troubling lack of standards and oversight.

Whether that’s an abyss you’re willing to wade into for the sake of high-tech, next-level masking is up to you.

-

Entertainment7 days ago

Entertainment7 days ago‘Interior Chinatown’ review: A very ambitious, very meta police procedural spoof

-

Entertainment6 days ago

Entertainment6 days agoEarth’s mini moon could be a chunk of the big moon, scientists say

-

Entertainment6 days ago

Entertainment6 days agoThe space station is leaking. Why it hasn’t imperiled the mission.

-

Entertainment5 days ago

Entertainment5 days ago‘Dune: Prophecy’ review: The Bene Gesserit shine in this sci-fi showstopper

-

Entertainment4 days ago

Entertainment4 days agoBlack Friday 2024: The greatest early deals in Australia – live now

-

Entertainment3 days ago

Entertainment3 days agoHow to watch ‘Smile 2’ at home: When is it streaming?

-

Entertainment3 days ago

Entertainment3 days ago‘Wicked’ review: Ariana Grande and Cynthia Erivo aspire to movie musical magic

-

Entertainment2 days ago

Entertainment2 days agoA24 is selling chocolate now. But what would their films actually taste like?