Business

With $160 million in new funding, Freenome looks to commercialize its blood test to detect colorectal cancer

One of the major problems that technology companies working to find a cure for cancer need to solve is finding a safe, minimally invasive way to detect cancers early.

Almost all cancer screening will eventually require a biopsy, but determining whether that’s necessary in the early stages of cancer can mean the difference between life and death.

It’s one of the reasons why investors have spent hundreds of millions if not billions of dollars to find a reliable way to detect cancer from simple procedures like a blood draw. And it’s why they’re investing more than $160 million in the South San Francisco-based startup, Freenome.

“If I could do it with less money and do it responsibly, I would,” says Gabriel Otte, Freenome’s founder and chief executive officer.

Since the company launched in 2014, it has been developing a test that combines machine learning with the development of proprietary assays to test for different types of cancer. The company’s research started in prostate cancer, but it has since turned its focus to colorectal cancer.

It’s a strain of the disease that has already been proven to respond well to early diagnosis and treatment, whereas other types of cancer are less well understood in their earliest stages, according to Otte.

By drawing samples of cell-free DNA from the blood, and treating it with methylation and protein biomarkers, the company is able to apply machine learning techniques to identify additive signatures that can increase the accuracy of early cancer detection tests.

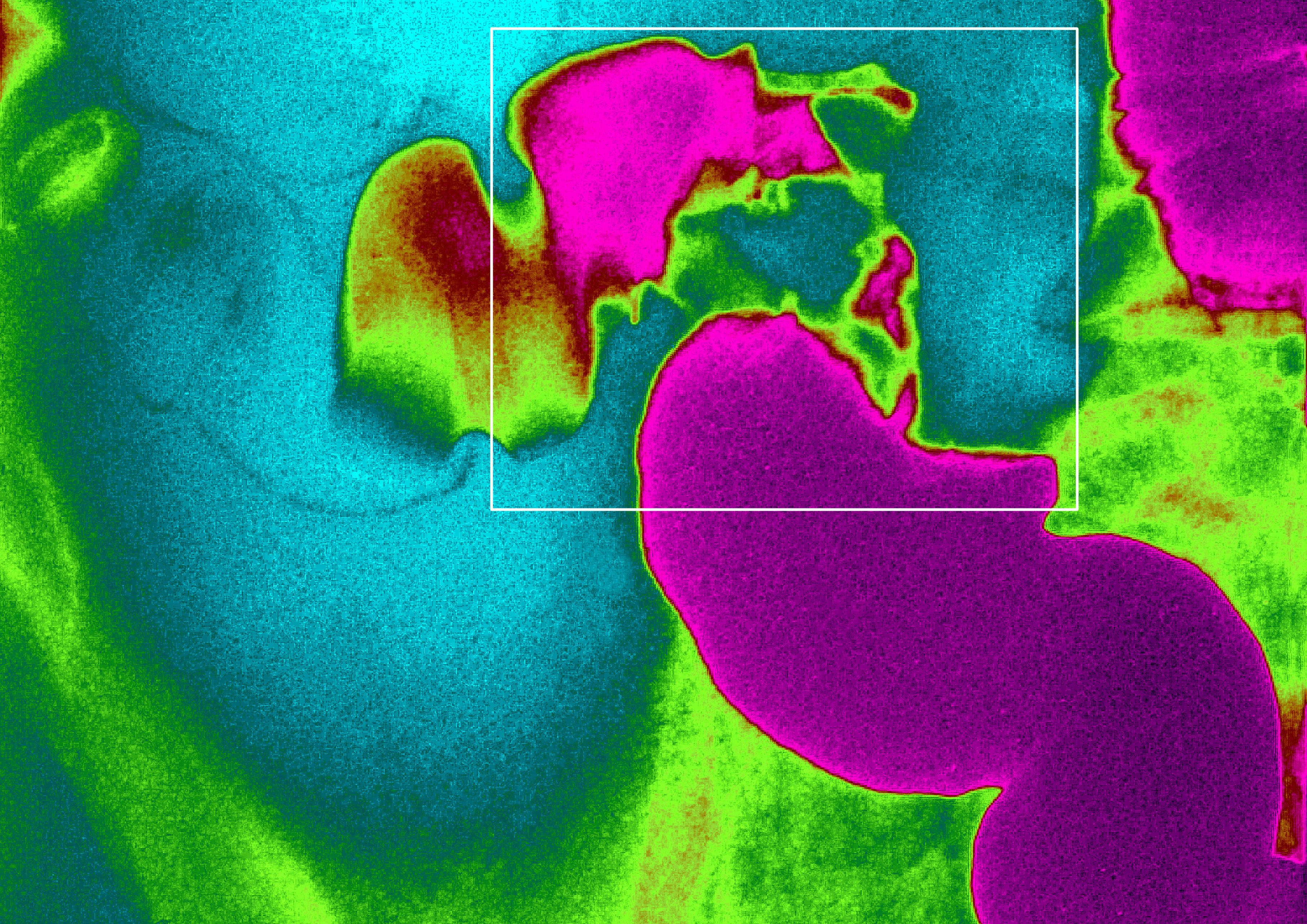

Cancer of the colon, x-ray, sigmoid colon cancer, frontal abdominal x-ray (Photo By BSIP/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

By using multiple inputs rather than looking for just genetic material coming off of tumors, the company says that its tests can detect cancer earlier than traditional tests that are more invasive and can miss early signs of the disease.

Colorectal cancer, which is the second most lethal cancer in the U.S., has a 90% five-year relative survival rate when it’s detected early, according to data from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program, cited by the company.

“We get this image in our head of a magical drug or using the immune system to kill a tumor. While drugs are an important part and will continue to play an important part… the difference between early detection and late-stage detection is life or death,” says Otte.

Freenome has data on several types of cancers and has looked at tests for over seven different targets — including colorectal and prostate cancer. But the company decided not to pursue a test for multiple cancer types because if they launched one, it would not get used, Otte said.

“For the vast majority of cancer types today you wouldn’t do anything differently if you detected it early,” says Otte. “We haven’t developed what is the medical standard that we would apply to such an incident.”

Competitors in the diagnostics market disagree. Grail, a startup also working in the diagnostics, space has raised $1.5 billion for its technology that screens for multiple cancers. The company even announced results earlier this year that showed promising advances for its technology. According to the company, data showed Grail’s still-in-development multi-cancer blood test detected strong signals for 12 deadly cancer types at early stages with a very high specificity of at least 99% (or a false positive rate of 1% or less). And the test identified where the cancer originated in the body (the tissue of origin) with high accuracy.

Thrive Earlier Detection, which raised over $100 million in May, is another company taking the approach of looking at multiple cancer screens.

For Otte the results may be impressive, but without a standard of care to follow, the test results are fairly meaningless.

“It’s not to say that I’m not a fan of people going after multi-stage cancer,” says Otte. “It’s a long road to see that that works and that helps.”

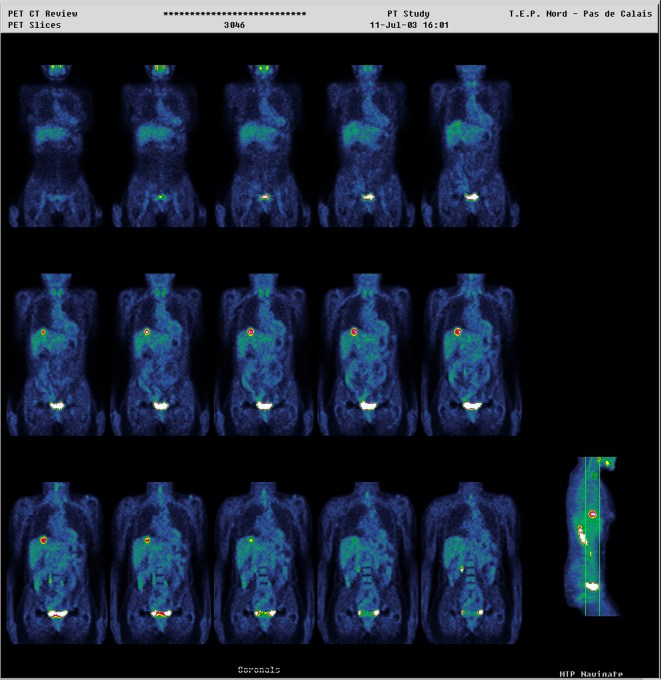

Institute of Nuclear Medicine, University Hospital of Lille, France. Pet Scan Positron Emission Tomography. Colorectal Carcinoma. Hepatic Lesions. (Photo By BSIP/UIG Via Getty Images)

The new financing for Freenome comes from RA Capital Management and Polaris Partners. The two investors were joined by funds advised by T. Rowe Price Associates, Perceptive Advisors, Roche Venture Fund, Kaiser Permanente Ventures and the American Cancer Society’s own impact investment arm, BrightEdge Ventures.

Previous investors, who put in an initial $78 million to fund Freenome’s work, also participated in the round. They included: Andreessen Horowitz, GV (formerly Google Ventures), Data Collective Venture Capital, Section 32 and Verily Life Sciences (a subsidiary of Alphabet focused on life sciences and healthcare).

Freenome said the money would be used for a validation study and would then submit an application for its colorectal cancer screening test to both the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) under the Parallel Review Program.

“The biggest hurdle [to a company’s success] is reimbursement,” says Otte. “We’re talking about Medicare coverage is going to be no more than $500… so a test needs to be significantly under $500 mark to make a significant business. [That means it] has to have clinical utility. That’s why colorectal cancer is the right move for us… payers are going to be amenable to a test like ours. It’s a big hurdle to generate enough data over enough time to show that your test results in a better patient outcome.”

Again and again, the company’s investors come back to the need for early detection to be a component of a cure for the world’s deadliest diseases and it’s something that Freenome’s chief executive also stresses.

“The most affordable and effective treatment for metastatic cancer is to detect it early, when the tumor is still small and local, and we can cure it with surgery. It’s with that vision that we have invested in Freenome,” said Peter Kolchinsky, managing partner of RA Capital.

The company differentiates itself not just in its approach to target single cancers with a test, but also in its use of multiple inputs beyond the genetic material given off by the cancer cell itself, according to Otte.

He sees one of the limiting factors to the success of other approaches as their inability to collect enough genetic material to produce accurate enough samples — even when those samples are enhanced by machine learning.

“We don’t believe that CT DNA is actually going to solve this problem,” says Otte. “It comes down to physics… In early disease there are very few fragments of DNA that will come from the tumor. At that low concentration [roughly] .01%… To take the appropriate amount of blood. If you were to collect 80 ML it would be… To get to 90% you would have to collect 300MLs.”

Once you have identified a disease, then you can begin to treat it, but you have to have a correct diagnosis. The best drugs, which can bring someone with Stage 4 lung cancer who is at the brink of death back to perfect health, only work in a small percentage of patients. The best approach is to treat the patient before they ever need a miracle cure, says Otte.

“When I talk about curing cancer, the cure comes from early detection followed by early prevention and treatment,” he says.

-

Entertainment6 days ago

Entertainment6 days agoOpenAI’s plan to make ChatGPT the ‘everything app’ has never been more clear

-

Entertainment5 days ago

Entertainment5 days ago‘The Last Showgirl’ review: Pamela Anderson leads a shattering ensemble as an aging burlesque entertainer

-

Entertainment6 days ago

Entertainment6 days agoHow to watch NFL Christmas Gameday and Beyoncé halftime

-

Entertainment5 days ago

Entertainment5 days agoPolyamorous influencer breakups: What happens when hypervisible relationships end

-

Entertainment4 days ago

Entertainment4 days ago‘The Room Next Door’ review: Tilda Swinton and Julianne Moore are magnificent

-

Entertainment3 days ago

Entertainment3 days ago‘The Wild Robot’ and ‘Flow’ are quietly revolutionary climate change films

-

Entertainment4 days ago

Entertainment4 days agoCES 2025 preview: What to expect

-

Entertainment3 days ago

Entertainment3 days agoMars is littered with junk. Historians want to save it.